Wequiock Falls

Steven Dutch, Professor Emeritus, Natural and Applied Sciences, University of Wisconsin - Green Bay

|

|

|

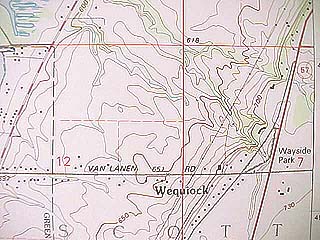

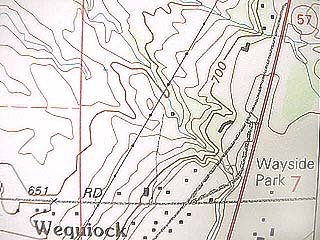

Location: Wayside 5 km NNE of the UW-Green Bay campus at the intersection of Van Lanen Road and State Highway 57. SE 1/4, NW 1/4 Section 7, T24N, R22E, Green Bay East 7.5' Quadrangle. |

|

Closeup of the map area. |

|

At Wequiock Falls, the Silurian Mayville dolomite overlies the Brainard and Fort Atkinson Members of the Late Ordovician Maquoketa Formation. The rocks of the Maquoketa Formation are generally easily eroded and less resistant than the overlying Silurian dolomites. |

| This outcrop is one of the better and more accessible of those exposed as streams flowing over the escarpment cut away the most resistant Silurian beds. |  |

The panorama below shows the falls at left, groundwater seepage and collapsed blocks. The contact between the buff Silurian rocks and the blue-gray Maquoketa formation is obvious.

|

A cross-section along Wequiock Creek. |

|

The lip of the falls is formed by 3 to 4 meters of gray medium-to-coarse-grained dolomite characteristic of the Mayville dolomite (the light thick band at the top of the bluff). Beyond the falls, ice on the cliff shows where ground water is seeping out of the rocks. |

|

In this warm-weather view, water is not only flowing over the falls but running out of the rocks as well. The Maquoketa Formation below the lip of the falls consists of blue-gray shaly dolomite. The blue-gray color is due to volcanic ash derived from the Appalchians and transported far inland by winds and currents. |

|

Like all waterfalls, Wequiock Falls retreats by undermining soft rocks, causing the lip of the falls to collapse on occasion. Here we see a recent collapse. |

Wequiock Gorge

|

Looking down the gorge of Wequiock Creek. In 11,000 years, Wequiock Falls has retreated about 200 meters, an average rate of a meter per 55 years. In the same time, Niagara Falls, which has a bit more water, has retreated 11 kilometers, an average of a meter per year or 55 times faster. |

|

A winter view looking up the gorge from Bay Settlement Road |

|

An early spring view looking up the gorge from Bay Settlement Road |

|

In the summer the creek is often dry. Here we see the dry falls from below with the stagnant plunge pool at the base. |

|

A closer view of the overhanging Silurian dolostone, the undercut Maquoketa Formation, and the plunge pool. |

Looking downstream when the trees are bare, the start of Wequiock Gorge is visible. When the ice first retreated from Northeast Wisconsin about 11,000 years ago, the falls originally flowed over the edge of the escarpment. The contrast between the bluish Maquoketa Formation and the buff Silurian rocks is obvious.

The Lower Gorge

|

North edge of the gorge from Bay Settlement Road |

|

North edge of the gorge from the stream. |

|

South edge of the gorge from the stream. |

|

South edge of the gorge looking back from below the escarpment. |

|

Maquoketa outcrops and imbricated pebbles about 200 meters below the escarpment. |

|

Imbricated Maquoketa cobbles in the stream bed. |

Wequiock Falls is somewhat unusual. There are not as many falls along the Silurian Escrapment as one might expect because the bedrock dips gently east and the land surface is a dip slope. Ideally, the drainage divide should be at the edge of the escarpment with streams flowing east to Lake Michigan. In the case of Wequiock Creek, there is a low moraine to the east (shown in the panorama below) that forms a drainage divide, so that Wequiock Creek drains the area between the moraine and the escarpment.

The drive up Bay Settlement Road takes us along the edge of the Silurian escarpment, commonly, though not entirely accurately, called the Niagara Escarpment. The Silurian escarpment emerges from beneath glacial drift south of Lake Winnebago and forms a line of prominent bluffs from there north to the tip of the Door Peninsula, which is a drift-mantled cuesta with a gently east-sloping surface. The escarpment wraps around the Michigan Basin, sometimes concealed by drift or submerged. The escarpment then curves east across Ontario and into New York. Niagara Falls flows over the Silurian Escarpment, but the rocks at Niagara Falls are mid- to upper Silurian, in contrast to the lowest Silurian rocks exposed here.

Structurally, eastern Wisconsin is transitional between the Wisconsin Arch and the Michigan Basin. The rocks are homoclinal with a gentle eastward dip of a degree or less and thicken to the east. Because the Silurian escarpment is the edge of an east-sloping cuesta, the drainage divide usually lies quite close to the escarpment. Thus, waterfalls are uncommon along the escarpment and Wequiock is the only one in the Green Bay area on public land. The falls have retreated about 200 meters in the 11,000 years since the ice retreated, about one meter in 55 years (compared to 11 kilometers, or 1 meter per year for Niagara Falls in about the same time). The falls retreat by undermining the soft Maquoketa rocks, and numerous caved blocks of massive dolomite can be seen in the gorge. There is a well-developed plunge pool at the base of the falls. The falls are often dry in late summer and early fall, and have only a small volume much of the rest of the time. After heavy rains and during snowmelt, however, their volume is impressive.

The lip of Wequiock Falls consists of about 3 meters of blocky dolomite of the earliest Silurian Mayville Formation, underlain by blue-gray shaly dolomite of the Brainard Member of the late Ordovician Maquoketa Formation. The Mayville Dolomite is a light-gray, fine-grained, medium to thick bedded dolostone with chert nodules. Fossils are not common and consist mostly of stromatoporoids, favasitid corals, and the brachiopod Virgiana. Conodont stratigraphy places the Ordovician-Silurian boundary at about the base of the dolomite. The Mayville-Brainard contact is disconformable, and an iron formation, the Neda, occurs locally between them. It is not present at this locality but occurs as an iron-rich clay layer at Bayshore County Park 10 km north of here, and as about half a meter of oolitic hematite at Kittel Falls (on private land) 18 km to the south.

The Maquoketa Formation

The Maquoketa Formation is Late Ordovician in age and is widely recognized in the upper Midwest. It is given group status in Illinois and Indiana. In Wisconsin, it is subdivided in ascending order into the Scales Shale, Fort Atkinson, and the Brainard Shale Members. The shales and argillaceous dolostones of the Maquoketa Formation are the distal edge of an extensive clastic wedge that was shed westward from the Taconic Mountains. A number of bentonite beds have been recognized in northeastern Wisconsin but none correlating with the well-known middle Ordovician beds found throughout the midcontinent. Those beds may have been deposited when the Wisconsin Arch was subaerial, and may thus be absent in this region.

The Scales Shale usually is covered by Pleistocene drift and lies near or below bay level. In excavations or poor exposures, it consists of gray-blue shale and argillaceous dolostone, sometimes with gypsum nodules (Stieglitz and Allen, 1980). The same authors describe the Fort Atkinson as dolostone and dolomitic limestone with interbeds of calcareous clay, and the Brainard as calcareous mudstone with interbeds of dolomitic shale and argillaceous dolostone. Allen (1980) discusses the paleoecology and depositional history of the Fort Atkinson. Brachiopods, bryozoans, tabulate corals, and solitary rugose corals dominate the fauna. Sivon (1980) and Fosburgh (1984) have also studied the Wequiock Falls section.

The straightness of the escarpment strongly hints at joint control, but the principal joint sets in this region trend ENE and SE, whereas the escarpment trends NNE. Outcrops on the escarpment typically have a serrate plan on a scale of 1-10 meters, governed by the ENE and SE joints. Joints with NNE orientation do occur, but infrequently. The author has an aerial photograph of the escarpment taken near Sturgeon Bay where joints are clearly visible through a thin snow cover. The overwhelming majority of joints in the picture belong to the ENE and SE sets, but there are a couple of joints parallel to the escarpment running the entire width of the view. Thus, the orientation of the escarpment may be governed by a small number of long master fractures close to the ice flow direction in the Green Bay lobe, but the joints themselves may have been obliterated by ice plucking or by block collapse after ice retreat.

Silurian outcrops occur as far south as the UWGB campus and the escarpment has subdued topographic expression for about a kilometer further south. From there south to Scray Hill (marked by a prominent cluster of radio towers) there are no Silurian outcrops. Well logs show a buried valley at least 60 meters deep and 11 km wide extending SE to Lake Michigan. This is one of a number of deep valleys cut through the escarpment (Figure 3). The most prominent of these is the gap at Sturgeon Bay which nearly cuts the Door Peninsula in two (a canal joins Green Bay to Lake Michigan). Most of the other valleys have been nearly filled with Pleistocene deposits and now have very subdued topographic expression. Channels were cut into the Pleistocene fill by outflow from Glacial Lake Oshkosh but the valleys themselves must be pre-Pleistocene. Their SE trend suggests structural control by one of the regional joint sets.

Systemic boundary between the Ordovician and Silurian strata. Wequiock Creek flows over the basal beds of the Silurian Mayville Dolomite that cap the rim of the Niagara Escarpment at this location. Green and greenish-blue shales and carbonates of the Maquoketa Formation are exposed in the plunge pool of the waterfall. Excellent fossil collecting location.

Introduction The Maquoketa Formation is Late Ordovician in age and was named by White (1870) from outcrops along the Little Maquoketa River in Iowa. The predominantly shaly sequence is distinctive in the dominantly sandstone-carbonate rocks of the region. It is widely recognized in the upper Midwest and is given group status in Illinois and Indiana. In Wisconsin, it is subdivided in ascending order into the Scales Shale, Fort Atkinson, and the Brainard Shale Members. The unit forms the bedrock beneath much of the Green Bay and Fox River lowland east of the escarpment. The best outcrops occur where streams flowing westward toward the lowland have exposed it by cutting into the escarpment. Here, Wequiock Creek has eroded eastward about 80 meters since the last retreat of Pleistocene ice from Green Bay. The Neda Formation, a red shale and oolitic ironstone unit that occurs between the Maquoketa and the underlying Mayville Dolomite, is not present at this location. The Mayville Dolomite that forms the escarpment cap, is Early Silurian in age and was named by Chamberlin in 1877 for outcrops in the vicinity of Mayville, Wisconsin. The unit is widely recognized in eastern Wisconsin. The Mayville is the basal unit of a thick sequence of Silurian carbonate formations that form the Door Peninsula and that dip gently eastward under Lake Michigan. This formation is an important aquifer throughout the region.

Lithologic Descriptions The Scales Shale usually is covered by Pleistocene drift and lies at or below bay level. In excavations or poor exposures, it consists of gray-blue shale and argillaceous dolostone, sometimes with gypsum nodules (Stieglitz and Allen, 1980). The same authors describe the Fort Atkinson as dolostone and dolomitic limestone with interbeds of calcareous clay, and the Brainard as calcareous mudstone with interbeds of dolomitic shale and argillaceous dolostone. Allen (1980) discusses the paleoecology and depositional history of the Fort Atkinson. She notes several hardgrounds and provides a fossil list. Brachiopods, bryozoans, tabulate corals, and solitary rugose corals dominate the fauna. Sivon (1980) and Fosburgh (1984) have also studied the Wequiock Falls section. The Mayville Dolomite is a light-gray, fine-grained, medium to thick bedded dolostone with chert nodules. Fossils are not common and consist mostly of stromatoporoids, favasitid corals, and the brachiopod Virgiana.

Environmental Interpretation The shales and argillaceous dolostones of the Maquoketa Formation are the distal edge of an extensive clastic wedge that was shed westward from the Taconic Mountains. Sedimentary structures and fossil assemblages indicate that the sediments that form the Fort Atkinson here, collected a mosaic of environments on a shallow subtidal shelf that was subjected to considerable water turbulence (Allen, 1980). The massive mudstones of the Brainard suggest greater influxes of fine clastics and somewhat deeper water and/or lower energy conditions. The upper thin bedded dolostone, usually placed at the top of the Brainard, marks less turbid conditions. In the past, there has been some uncertainty about the exact placement of the Brainard-Mayville contact, and the stratigraphic assignment of the Neda Formation. Since the Neda is missing at this location, the contact must be disconformable. A stratigraphic study of the conodonts of the sequence between the mudstone of the Brainard and the Mayville is presently underway. The relatively clean dolostones of the Mayville formed in stable subtidal and open marine environments. The entire Silurian carbonate sequence collected on the margin of the Michigan Basin and thickens notably eastward.

Return to Geology of Wisconsin Index

Return to Geologic Localities Index

Return to Professor Dutch's Home Page

Created 21 June 1999, Last Update 11 January 2020